Graphic by Shelby Cotta

International students watch restrictions loosen in Gainesville as COVID-19 rages at home

Seventeen UF international students from 13 countries witnessed inequality, civil unrest and vaccine shortages

By Alexandra Harris and Isabella Douglas

After a year of timing phone calls between time zones, punctuated by pleas to “stay safe” as if it could be the last goodbye with their loved ones, international students at UF are watching their peers in Gainesville return to pre-COVID life — while the virus still wreaks havoc back home.

There have been over 180 million confirmed cases of COVID-19 worldwide since December 2020, according to the World Health Organization. For many Americans who now have access to almost 300 million vaccines, the pandemic is slowing down. This is not true for many countries outside of the US.

Almost 6,000 international students from 140 countries, more than half of them graduate students, attended UF in Fall 2020, according to the UF International Center. Students witnessed inequality, civil unrest and vaccine shortages while in their home countries. Others read about their country’s pandemic in the news and listened to their loved ones overseas.

Transformed by the tragedies of the COVID-19 pandemic, international students grieved not only for loved ones but their countries.

Dr. Sumita Bhaduri-McIntosh, UF associate professor and chief of infectious diseases in the department of pediatrics, believes the world can’t let its guard down without global vaccination rates rising.

With her parents in India, she watched from afar as their lives were threatened and her home country devastated.

“When you have a virus that has the potential to evolve and evade vaccines over time, it endangers not just the people in those countries without access to vaccines, but also those with access to vaccines,” Bhaduri-McIntosh said.

Even with nearly half of the U.S. fully vaccinated, she said there is little hope for the near future if the virus is not controlled elsewhere. Only 1% of people in low-income countries have been vaccinated with one dose, according to Our World in Data.

“Which makes the access to vaccines that much more important in other countries worldwide,” she said. “It’s not just enough to have access to vaccines and for most people to take the vaccines in the Western world.”

Grief surfaced tears for UF international students who lost their families to the pandemic.

Yet laughter and smiles persevered as others found humor in solemn situations.

On May 5, 2020, Gabrielle Quadrado tied the knot with her husband, Matheus Bose, in her hometown Rio Grande do Sul State — just as Brazil teetered on the brink of a grueling descent into chaos and tragedy.

“[It was] really early in the pandemic and we didn’t know how to act,” Quadrado, a 25-year-old climate science Ph.D. student said. “We were so scared.”

As soon as she received her acceptance letter to UF for her Ph.D. in climate science, she set a date.

Even with love blossoming, loss was around the corner. Away in Ecuador awaiting visa approval, Quadrado received crushing news from home. Her uncle, Leandro Pereira, died from COVID-19 at 46 years old on December 17, 2020.

“So young,” her voice broke. “He had a whole life ahead of him.”

While visiting her family before coming to the U.S., she said she wouldn’t hug anyone because of the virus. On the last day she spent in her hometown, she made an exception.

“I decided I was going to give a hug on my grandma and also my uncle,” she said. “And I didn’t know that was our last hug.”

Bolivia

While Adriana Rojas Muriel, a 22-year-old UF biology junior, spent her summer alone in Gainesville, her mind was on Bolivia.

Instead of lively Saturday conversations during meals with her mother, sisters and grandmothers in her hometown of Santa Cruz, she listened to them describe Bolivia’s vaccine shortages, driving bans and protests against government corruption happening 3,000 miles away.

In Gainesville, she pushed through online classes and her independent research about Leishmaniasis, a parasitic disease in Bolivia.

“Stay at the worst point of the pandemic — where you were unemployed, where one of your families was at the hospital, at your worst point — that's the point that Bolivia is living in right now and is living every day and has been living for more than a year,” Rojas Muriel said.

Over 444,000 Bolivians have tested positive for COVID-19 and over 16,900 have died, according to the World Health Organization.

Rojas Muriel lived in Santa Cruz de la Sierra for 18 years before moving to Gainesville in May 2018, where she stayed through the pandemic. She planned to visit home this summer, but her parents thought she had a better chance of surviving the virus with the U.S. healthcare system.

Bolivia’s hospitals are running out of oxygen supplies and hospital beds for COVID-19 patients, according to the Human Rights Watch.

Rojas Muriel saw Bolivian families break because of the deadly disease. Her 10-year-long friend’s father died of COVID-19 May 27.

Rojas Muriel’s father is still grieving the death of his best friend who died January 3.

"It's not about you not getting sick or you not getting COVID," Rojas Muriel said. "It's about others not getting it."

Rojas Muriel’s grandmother, an 80-year-old hospital director, received Sinopharm vaccines in April because of her age. Unvaccinated medical students still worked with COVID-19 patients in the same hospital.

In late May, anti-vaccination groups spread false information about “satanic” vaccines. As of June 7, confirmed cases of COVID-19 spiked, according to the WHO. Less than 16.5% of Bolivia’s population received at least one dose.

“I don’t like when people tell me here that they don’t want to receive a vaccine because they don’t want any side effects,” Rojas Muriel said. “I would die to take those vaccines that are not being utilized back to my country.”

While the virus still ravages the country, Rojas Muriel said many Bolivians also fear the crime that came with the pandemic.

Her family’s bicycles were stolen off the patio. She worried someone could break into her family’s home and threaten them.

During the pandemic, 74% of workers stopped working, according to a Gallup poll.

“In developing countries like mine...they need help from outside governments to interfere, to provide vaccinations, to provide food, to provide just some security in their life,” Rojas Muriel said.

Contact Isabella Douglas at idouglas@alligator.org. Follow her on Twitter @Ad_Scribendum.

Sarah Rojas, Fernando Rojas, Claudia Muriel, Mirko Rojas and Adriana Rojas Muriel (from left to right) in Adriana Rojas Muriel’s family home in Bolivia. (Photo courtesy to The Alligator)

Colombia

Dios de pan a quien no tiene dientes. God gives bread to the people who don’t have teeth.

The Spanish saying reminds Orlando Sanchez, a 31-year-old public health master’s student, of those who reject vaccines during shortages and crises. The Colombian international student witnessed some in Gainesville turn down the same life-saving vaccines his family and community needed back home. Sanchez lived in Barranquilla, Colombia for 30 years before moving to Gainesville in December.

In Colombia, there have been about 4 million confirmed cases of COVID-19 and over 108, 000 deaths, according to the World Health Organization. On average, about 27,000 new infections are reported each day.

The U.S. embassy in Colombia warned travelers about the mass protests against the government last June.

Colombian international UF students scoured for news about the pandemic and political instability tearing through their home country. As mass protests broke nightly curfews on the Colombian streets, the students fumed over the unequal vaccine access between their home country and Gainesville.

The 2020 protests against government corruption and income inequality repeatedly broke Colombia’s 6 p.m. to 6 a.m. curfew, which was set because of the high death toll.

Sanchez does not agree with what the government is doing.

“The answer is not the right or left-wing,” Sanchez said. “None of them is the answer.”

About 14% of Colombia’s population has been fully vaccinated, according to Our Data World.

Sanchez worked at a hospital in Barranquilla. From March to May 2020, the hospital was at full capacity without enough respirators, he said. The hospital directed people to other facilities because it ran out of oxygen tanks.

When patients were being treated, COVID-19 restrictions banned family visits.

While in Gainesville he checked his Facebook feed for news about Colombia and regularly called his family.

Daniel Acosta, a 30-year-old public health Ph.D. student, also watched from his screen in Gainesville as his country protested its government’s mishandling of the crisis.

“People that are protesting because the country is not really doing well and the prospects and the future of many is in jeopardy right now,” Acosta said. “Most of the population are not happy with some of the decisions from the government and I think the pandemic just exacerbated that.”

At age 27 he moved to Gainesville with a Colfuturo Latin American scholarship to pursue his Ph.D. in public health.

From 2017 to 2019, Acosta returned to Colombia once a year to reconnect with his Colombian family and culture. He grew up visiting the beaches and national parks of Barranquilla, but the pandemic has kept him from visiting for two years.

In January, Acosta received his full COVID-19 vaccination in Gainesville. It took three more months before his parents in Colombia received their first dose.

“It’s always a striking difference with the U.S.,” Acosta said. “Here we have so many vaccines we don't know what to do with them and basically [Colombia is] just still slowly rolling them out — a bunch of people still waiting for vaccines.”

Contact Isabella Douglas at idouglas@alligator.org. Follow her on Twitter @Ad_Scribendum.

Daniel Acosta smiles with his girlfriend at Tayrona National Natural Park in Colombia, eight months before moving to Gainesville. (Photo courtesy to The Alligator)

Guatemala

Ana Barrientos poses with her grandparents, Lylia Velásquez and Edgar Guevara, in her high school graduation cap and gown. (Photo courtesy to The Alligator)

At 4 years old, Ana Barrientos moved from Guatemala City to Gainesville. At age 22, the UF international studies senior received her second COVID-19 vaccination at UF’s Ben Hill Griffin Stadium in April.

Her grandparents, both 72, lived in Guatemala all of their lives. They too had to travel to Gainesville to receive vaccines in May and June.

Guatemala had over 301,000 COVID-19 cases and more than 9,000 deaths, according to the World Health Organization. Less than 1% of Guatemala’s population has been fully vaccinated.

The rest of Barrientos’s Guatemalan family hasn’t been able to get a vaccine. Concerns about the quality and expiration date of the vaccines are widespread, she said.

“It's a privilege to live in the United States. It's a privilege to have the vaccine already, for the pandemic almost to be over. That's almost unheard of in other places,” Barrientos said.

With the current numbers, the additional 10% of the Guatemalan population will be vaccinated in ten months if 11,000 people are vaccinated every day. With over 1,400 COVID-19 cases being recorded every day, the Barrientos family in Guatemala has been quarantining since the beginning of the pandemic.

When the pandemic started, Barrientos’s aunt experienced a lockdown in her neighborhood in Guatemala City, which the government blamed on a gas leak. She was told to stay indoors. It wasn’t until three weeks later her neighbors told her it was because of a COVID-19 outbreak.

”You're losing that cultural part of social interaction,” Barrientos said. “Especially for Latin American countries where the social interaction is such a big part of the culture.”

September is usually filled with parades, parties and feasts of traditional dishes to celebrate Guatemala’s independence from Spain. Celebrations were canceled last September due to the pandemic.

Barrientos' cousin is a medical student in Guatemala who works at a hospital. She tells her family hospitals are still overrun with COVID-19 patients and not enough resources to go around.

Miscommunication from the Guatemalan government hasn’t helped the crisis, Barrientos said.

“There was a promise of vaccines, and in the end, those vaccines were only available to certain people who had government connections and not necessarily to the general population,” Barrientos said.

Barrientos wants vaccine providers held accountable so her family can start getting vaccinated in their county.

When Barrientos thinks about graduating from UF, she worries. She faced visa complications at the beginning of the pandemic, which suggested international students would not be able to stay in the U.S. if they were online.

Although UF's International Center tried to support her, Barrientos felt like it wasn’t enough. She didn’t feel heard.

“There's a lot of red tape when it comes to immigration and I feel like that's not a conversation that's had very often,” Barrientos said. “The system is really skewed against people who want to immigrate to the U.S. legally.”

Contact Isabella Douglas at idouglas@alligator.org. Follow her on Twitter @Ad_Scribendum.

Saudi Arabia

Hussah Bubshait smiles outside Rochester, New York. She reunited with her family in Saudi Arabia for four months at the beginning of the pandemic. (Photo courtesy to The Alligator)

Hussah Bubshait woke up crying in her Gainesville apartment last July. Her sister in Saudi Arabia tested positive for COVID-19.

“I cried more than her,” Bubshait, a 35-year-old UF international nursing Ph.D. student, said. “You feel bad because you are away from your family, and even when they call you, they will not even tell you the whole truth.”

The country has about 492,700 confirmed cases of COVID-19 and over 7,800 deaths, according to the World Health Organization. About 5% of the population of Saudi Arabia has been fully vaccinated.

The pandemic allowed Bubshait to reunite with her family for four months at the beginning of lockdown. Since moving back to Gainesville, she’s struggled with the 7,000 miles separating her from her loved ones.

Bubshait was nine months pregnant with her second child when she moved to Gainesville from Dammam, Saudi Arabia with her husband in August 2019. She started her nursing Ph.D. at UF ten days after giving birth.

“It was very hard, in the beginning, to go out, or deal with others or talk with others,” Bubshait said. “Having two kids at home makes you feel lonely... and doing that first year of Ph.D.s, it was very hard.”

In November, Bubshait decided she would rather be locked down with her family.

She traveled with her husband and two children to Saudi Arabia. Her sisters, brothers and their families quarantined together in her parents’ house for four months. Her youngest child met their uncles, aunts and cousins for the first time.

“In Saudi Arabia, people are supportive to each other,” Bubshait said. “You will never feel lonely.”

She was required to download a Saudi Ministry of Health app called Tawakkalna, which provided a history of the individual’s COVID-19 status, alerted residents of curfews and GPS tracked them.

“You will never be allowed to go anywhere, even to the supermarket or shopping mall without this application,” Bubshait said.

Shoppers piled outside of mall doors trying to present their apps with a faulty internet connection, Bubshait said.

From March to May 2020, Saudi Arabia was in complete lockdown with curfews. Gatherings of more than 20 people in households were not allowed and facemasks were always required when outside homes.

Starting May 11, individuals who did not comply with COVID-19 regulations would be fined anywhere from $2,666 to $13,329.

The pandemic reduced the demand for oil and gas, causing economic pressure for Saudi Arabia. People across the country felt the effects of wages and job losses, including Bubshait’s cousin, who lost his job as a pilot.

Bubshait and her family returned to Gainesville in February to continue her classes. While Saudi Arabia closely monitored and enforced COVID-19 restrictions, the U.S took a different approach.

Despite being able to move more freely in Florida, she felt more isolated inside her home. Away from her support system, she stayed in her apartment with her kids and focused on her studies through Zoom.

Bubshait longs to return to Saudi Arabia after she completes her degree.

“I miss [my family] so much,” she wrote. “But I’m here for a goal and I have to finish it.”

Contact Isabella Douglas at idouglas@alligator.org. Follow her on Twitter @Ad_Scribendum.

Indonesia

Christa Geraldine witnessed privilege change how people experienced the pandemic. As an Indonesian UF online student, she recognized massive disparities between America and the over 17,000 islands that make up her home county.

Privilege determined who got the vaccine, which schools stayed open and which hospitals received supplies, she said.

The 25-year-old digital strategy student joined UF online from Indonesia at the beginning of the pandemic to earn her master’s degree. She works as an assistant lecturer of communication an hour outside of the capital, Jakarta, on Java Island.

Indonesia has over 2,300,000 confirmed cases of COVID-19 and about 61,000 deaths, according to the World Health Organization. Over 42,400,000 people have been fully vaccinated, less than 5% of the population of Indonesia.

Geraldine believes COVID-19 cases in Indonesia are higher and the government’s lack of transparency and information is to blame for unreported cases.

“For the last one and a half year we’ve been encountering undocumented cases from everywhere,” she said. “The number of the reported cases, they are so small when compared to the real exact number. We don’t even know the exact number.”

Geraldine believes the government lacked urgency in its response to the outbreaks.

Hospitals across the country floundered without supplies throughout the pandemic. Java and many smaller islands still struggle to stock their ventilators and oxygen.

The government’s goal to have 40.2 million health care workers, public officials and elderly citizens vaccinated by the end of April wasn’t accomplished, with 93% of health care workers and only about 8% of the elderly receiving the vaccine.

“The first world countries are pretty privileged to get the first vaccines and they have big doses of them,” Geraldine said. “It’s pretty easy compared to rural countries, especially underdeveloped countries.”

Against the advice of medical experts, the government prioritized vaccinating healthcare workers, public officials and working-class adults over elderly citizens.

In April, some local governments held vaccination events for business owners, employees and law enforcement. During this time, some non-priority individuals bargained and used their connections to illegally receive vaccines, Geraldine said.

“People who are privileged and have connections, they already get vaccinated because they sneak into the crowd and say, ‘I’m from this shop,’” Geraldine said.

Citizens under the age of 18, who are not prioritized, have access to the vaccine this way. Geraldine said the rich take advantage of the loophole.

“I can just slip in and say that, ‘Oh, I'm a relative of this shop so, can you please vaccinate me,’ and you will get through,” Geraldine said. “That's kind of the corruption, that's what’s happening in Indonesia.”

Areas with high tourism, like Bali, forced domestic visitors who violated the mask policy to do pushups. Last year, villagers were forced to dig COVID-19 graves as punishment for not abiding by the government's guidelines.

On Java, fines and punishments for not wearing a mask aren’t as commonplace. People often host parties and disobey safety protocols, she said.

“We’re not really protected because the awareness of wearing the mask here, like facial masks and other protective equipment are so low,” Geraldine said.

Contact Isabella Douglas at idouglas@alligator.org. Follow her on Twitter @Ad_Scribendum.

Christa Geraldine smiles in her home country Indonesia. She thinks of the rising COVID-19 cases going undocumented in the country. (Photo courtesy to The Alligator)

Pakistan

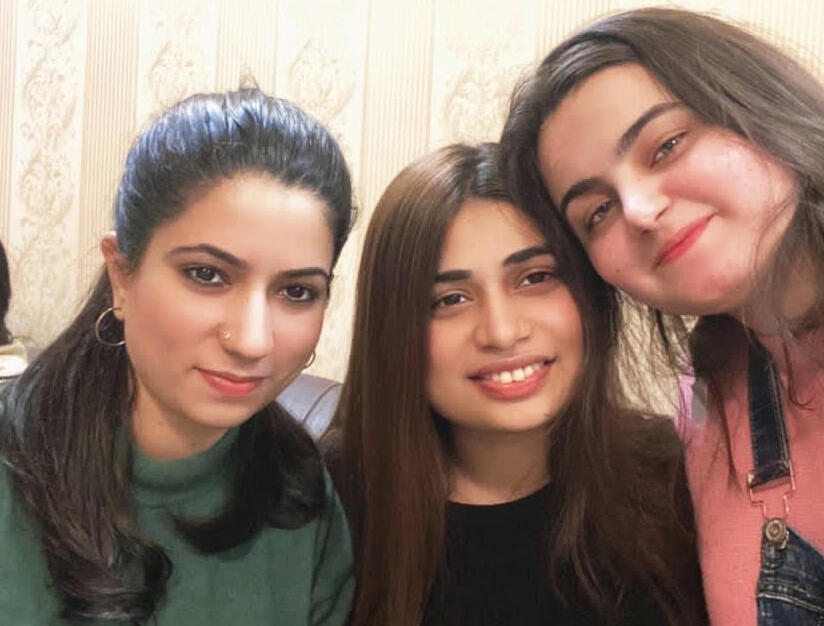

Rubab Ajmal (middle) smiles with her two sisters a day before her flight to the U.S from Lahore, Pakistan. (Photo Courtesy to The Alligator)

The morning after Rubab Ajmal received her COVID-19 vaccination at UF’s Ben Hill Griffin stadium, she woke up to a Facebook post about her childhood classmate dying of the deadly virus in Pakistan.

“It was so hard knowing that I'm at a place where I got the vaccine earlier,” Ajmal said. “Knowing their pain and not being there with them kind of makes you hate your own privilege.”

The 25-year-old agriculture and biological engineering master’s student lived in Lahore, Pakistan her whole life before moving to Gainesville in December 2020.

Pakistan has over 960,000 confirmed cases of COVID-19 and over 22,400 deaths, according to the World Health Organization. Over 17 million doses of the vaccine, less than 1.5% of the population of Pakistan.

Ajmal’s parents received their vaccines two weeks ago while her grandmother received the vaccine in Pakistan in May. On June 3, the government announced individuals 18 years or older could sign up for the vaccine.

After coming to the U.S. in the middle of the pandemic, Ajmal noticed similarities between her home and Gainesville.

“Lahore is just like the Florida of Pakistan,” Ajmal said.

In both countries, people are skeptical about the quality of vaccines and don’t want to wear masks.

Ajmal is disappointed when people refuse the vaccine that could have saved her friend and millions of others.

In Pakistan, lower-class people are jailed and fined for not wearing masks or social distancing, she said. For the rich, parties and social life persisted.

After months of isolation, she can’t wait to go home where she has her support system all in one city.

“I have been placed somewhere where I don't know anyone and I don't have anyone to fall back on,” Ajmal said. “Having a network and having a place where my roots were is something I miss the most.”

After months with no in-person classes and an empty campus, Ajmal reached out to UF’s CWC in March. Every week, she looked forward to relaxing outdoor activities with new friends and tips on how to cope during the pandemic.

As Ajmal spent her time at UF in online classes away from her family in Lahore, UF student Fahad Rafiq was deferred a semester and spent the pandemic in Pakistan.

Rafiq, a 32-year-old UF animal science Ph.D. student, lived in the city of Burewala for all his life before moving to Gainesville in May.

In spring, he took synchronous classes in Pakistan. The nine-hour time difference forced him to wake up close to midnight to attend morning classes.

Throughout the day he pleaded with his friends and family to ignore the stigma surrounding the COVID-19 vaccine in Pakistan. He heard a false rumor back home about the vaccine, where if people got vaccinated they would die in two years.

“All we can do is think of others when we are wearing masks or getting vaccinations,” Rafiq said. “It is not that we are doing it just for ourselves, we are thinking of the illness, the people who won’t recover.”

Rafiq said his country provided a mature response to the pandemic by implementing COVID-19 regulations set after the research of epidemiologists and scientists. The priority is the safety of Pakistanis.

“One life lost is too many,” Rafiq said.

Contact Isabella Douglas at idouglas@alligator.org. Follow her on Twitter @Ad_Scribendum.

Iran

After trying to get her Visa for 11 months, Pouneh Baniasad ended up stranded in a Turkish airport on her way to Gainesville.

Thirty minutes before her flight to the U.S., the Iranian international UF student was told she couldn’t board the plane. She spent three days in the airport alone in late December.

“They didn’t let me in and they didn’t answer me,” Baniasad said. “I was so confused and so tired.”

The 28-year-old UF Neuroscience Ph.D. student spent 11 months filing paperwork at embassies before booking the plane ticket. While Baniasad wouldn’t step foot inside the U.S until January, her mind stayed on the family she left in Tehran, Iran.

Wave after wave of COVID-19 cases struck Iran. The country has over 3 million confirmed cases and over 84,700 deaths, according to the World Health Organization.

She spent days in the airport emailing Iran’s neighboring embassies until she received an answer from Dubai. Nothing was wrong with her Visa, the embassy told her, so she booked another flight with a Qatari airline.

“Iranian students have a lot of problems just entering the USA,” Baniasad said. “Every step, every process is really scary for us because we can lose everything without any reason.”

With only 3.4% of the country fully vaccinated, the Iranian Minister of Health announced the emergency use of a second Iran-made COVID-19 vaccine June 30, only 16 days after authorizing use of its first.

Hearing about her friends’ relatives dying because of COVID-19 made Baniasad want people in the U.S. to appreciate what they have and get vaccinated to slow the spread of the virus.

“I’m not expecting that people in here understand what’s happening out there,” Baniasad said. “You really have to be in a country to see the suffering of the people.”

After traveling to secure her visa, Baniasad heard news that her father contracted the virus. He self-quarantined at home for two weeks until he was healthy.

In March, Baniasad got her first dose of the COVID-19 vaccine in Jacksonville. Two weeks later, she got her second dose in Gainesville. Her family in Iran still has not been vaccinated.

“I wish that I can send some vaccines to my parents,” Baniasad said. “Everytime they want to go out, I’m just scared...and I’m still asking them... ‘Please stay at home because I cannot stand if anything happened to you.’”

She received a Visa which allows her to travel back to Iran within two years and hopes to see her family in January. Some Iranians who travel to the U.S. haven't seen their families in ten years because of their single entry visa, she said.

She hopes the immigration nightmare is over, but worries about what will happen when she visits her family next year.

Contact Isabella Douglas at idouglas@alligator.org. Follow her on Twitter @Ad_Scribendum.

Pouneh Baniasad at her favorite museum, Moghadam Museum, in Tehran for her birthday. (Photo courtesy to The Alligator)

Argentina

Mariana Occhiuzzi and her team used to spend their work hours armed with a red clown nose, instruments and magic tricks while applying musical first-aid to the nurses and patients in the intensive care unit.

Now, the 43-year-old arts in medicine online UF graduate student composes music from a computer screen. Occhiuzzi would normally say the arts provide a brief moment of solace for Argentina’s Hospital Italiano de Buenos Aires, but she isn’t sure if the music is enough anymore.

Argentina has had over 4.5 million confirmed cases of COVID-19 and over 95,000 deaths. Only 4.3 million people are fully vaccinated, or 10.5% of the population, according to Our World in Data.

Argentina imposed a strict 8 p.m.- 6 a.m. curfew. It began a slow vaccine rollout in December 2020 with the Sputnik V vaccine for frontline workers and high-risk groups.

“There is a huge difference between the lockdowns in the United States and here,” she said. “Here you go to jail.”

People are still out on the streets risking the virus and arrest because they cannot afford to stay unemployed, she said. Many pivoted to selling food, clothing and instruments to make ends meet.

“This is a very bad moment,” Occhiuzzi said. “This is the worst peak for the pandemic in Argentina.”

The word “exhaustion” is constantly on the lips of nurses Occhiuzzi once worked alongside. Psychiatric and sick leaves reached new peaks, she said.

Without time to grieve for those they were unable to save, the caregivers became the cared for. Despite the relentless efforts to treat their colleagues, five Hospital Italiano de Buenos Aires nurses have died from COVID-19, she said.

Many people avoid care for other medical conditions out of fear, she said.

She returned to Chile when the pandemic hit to be in her husband’s hometown. Although she’s one hour from her family in Argentina, closed borders keep them apart.

Watching from quarantine in Latin America, she said it is surprising to see people reject vaccinations in the U.S.

“I don’t get mad at them,” she said. “But I don’t understand them.”

The pandemic has unveiled a lack of empathy for others — there is an entire world beyond the borders of the United States, she said.

If their loved ones were dying next to them, then they might change their minds, she said.

Contact Alexandra Harris at aharris@alligator.org. Follow her on Twitter @harris_ alex_ m.

Mariana Occhiuzzi (right), a 43-year-old arts in medicine graduate student, hugs a nurse during her project Susurro de Colibrí. (Photo courtesy to The Alligator)

Taiwan

It will take the stars aligning for the people of Taiwan to get COVID-19 vaccinated, according to Jia-Yi Ling. The UF international student said the only person with any influence is a fortunetelling astrologer.

Only about 10.3% of the population of Taiwan has been vaccinated with at least one dose, according to Our World in Data. Most only have access to the first dose due to shortages.

There have been over 15,000 cases and 680 deaths, according to the Taiwan CDC.

Taiwan had successfully fended the pandemic off, largely preventing it from entering its borders until a spike in cases in May. Daily cases increased rapidly until May 28, reaching a peak of about 600 cases, according to Our World in Data.

Ling, 27-year-old agriculture and biological engineering UF graduate student, stayed updated on her home country through her friend, 28-year-old Taiwan resident Chun-Ying Huang.

“Before this, COVID-19 was something happening to the outside world,” Huang said.

Strict border control and eager mask wearers resulted in Taiwan’s previous success, according to the Washington Post.

Even high-risk people hesitated to take the AstraZeneca vaccine. They feel it is inferior or have misconceptions about it, Huang said. A single dose of the AstraZeneca vaccine has an efficacy of 60-70%, with two doses at 85-90% effective, according to the British Medical Journal.

People in Taiwan compared the efficacy rates of vaccines on social media and decided they do not want AstraZeneca, even though it is the only option, Huang said.

Others worried about the blood clotting risk, he said, which the European Medicines Agency found a link with the AstraZeneca vaccine. EMA stated the overall benefits of the vaccine in preventing COVID-19 outweighed the rare side effect, with 18 fatal cases reported out of 25 million vaccinations.

Huang got his first dose of the AstraZeneca vaccine this spring because he works in a lab.

With a pre-existing deep distrust for the government, Huang said the skepticism intensified because the President of Taiwan has yet to get vaccinated.

Huang and Ling joked that the moms and grandmas of Taiwan find the fortune teller more convincing than the president.

“If she can take the vaccine on TV, I think all the skepticism will disappear,” Huang said.

Fearful of severe side effects, Ling’s friends working in a hospital are not getting vaccinated.

“Because they are very busy with working,” she said. “They don’t feel okay to take one day off.”

The hospitals in Taipei are reaching capacity, but have not collapsed, said Health Minister Chen Shih-chung, according to Focus Taiwan - CNA English News.

Huang read aloud a Bloomberg article that he said explains almost everything in Taiwan: All the virus had to do was get through the border.

Even Taiwan’s fortuneteller doesn’t see the country’s immunity lasting. Ling’s mother almost cried with the fortuneteller’s grave warning of mass Taiwanese deaths, she said.

Contact Alexandra Harris at aharris@alligator.org. Follow her on Twitter @harris_ alex_ m.

Peru

In the desert of Lima, Peru, rain is as scarce as hope.

The people heard a noise May 24 they have not heard for over 60 years: Whipping cracks of lightning illuminated the skies of Lima as rain pelted down.

Surrounded by death and disease, they asked themselves, “Is this the end of the world?”

Peru has the worst COVID-19 death rate per capita in the world, according to data by Johns Hopkins University. There have been over 2 million cases and over 190,000 deaths, according to the World Health Organization. Only 9.2% of Peru’s population is fully vaccinated, according to Our World in Data.

Every five minutes a Peruvian died from COVID-19 during May, Fiorella Guerrero said.

Guerrero, a 36-year-old UF rehabilitation sciences graduate student, serves as a board director for Warmakuna Hope, a Christian organization providing free physical and speech therapy to children in impoverished areas.

She stayed in the U.S. with her husband after visiting Lima for Christmas.

To be able to eat and survive, people in Peru cannot go into quarantine, Guerrero said. The economy will completely collapse if they can no longer work.

Two million Peruvians have lost their jobs during the pandemic and a third are living in poverty, according to Al Jazeera.

“When you are under the line of poverty, if you lose your job, you don’t have any savings to support you,” Guerrero said.

When Peru implemented a strict lockdown for six months, many families lost their means of survival, she said.

The most widely available vaccine in Peru, Sinopharm, has a 79% efficacy against hospitalization after two doses. The efficacy rate is lower than Pfizer and Moderna’s, which both have a 94% efficacy.

Guerrero believes her mother-in-law, a gynecologist, caught COVID-19 from a patient. Three weeks prior, she had received her first dose of the Sinopharm vaccine.

“She did not even have a bed in the hospital because they were not available,” she said.

Her mother-in-law struggled on oxygen for six weeks. Eventually, as a doctor, she was able to treat herself at home, Guerrero said.

Patients with chronic diseases or emergencies have nowhere to turn because the hospitals are so packed with COVID-19 patients. Guerrero’s father has cancer, diabetes and chronic kidney disease, and he has not been able to receive care.

“The Peruvian health system has collapsed,” she said.

The doctors must choose who to save; older patients are removed from intensive care services if someone younger or with a greater probability of survival arrives at the hospital, she said.

Guerrero’s friend and Warmakuna Hope volunteer, Mauricio Cordova, installed locally developed Peruvian ventilators into hospitals.

The low-cost ventilators can be rapidly produced to treat patients with COVID-19 and severe acute respiratory distress syndrome, according to Pontificia Universidad Católica del Perú.

“He was telling me, ‘I really think it’s the end of the world. I see death all over the place,’” she said. “He goes into the hospitals and sometimes he sees dead bodies in black bags.”

Contact Alexandra Harris at aharris@alligator.org. Follow her on Twitter @harris_ alex_ m.

Fiorella Guerrero, (second from left) a 36-year-old UF rehabilitation sciences graduate student, celebrates Christmas with others at Warmakuna Hope in Lima, Peru. (Photo courtesy to The Alligator)

United Kingdom

The bustling streets of London, once full of chattering people and scuttling cars, fell into silence as police prowled for lockdown violators.

“London was a ghost town,” Vini Mariani, 28-year-old UF physiology graduate student, said.

The United Kingdom totaled over 4.7 million COVID-19 cases and over 128,000 deaths for a population of almost 67 million people with 48% of the UK population fully vaccinated, according to Our World in Data.

With the highly transmissible Delta variant accounting for 99% of cases in the UK, daily cases spiked ten times the average in May. Despite a successful vaccination campaign, 20,000 new cases averaged daily, according to CBS News.

Mariani, born in South Brazil, spent seven months stranded in London working toward his master’s from UF. He returned to Gainesville in August 2020.

Every flight he booked to close the more than 5,000-mile gap between his family in Gainesville and Brazil was canceled.

His 65-year-old mom had emergency heart surgery in a Brazilian hospital in February. Filled with fear and overwhelmed by a major surgery in a packed hospital, the virus didn’t stop Mariani’s 66-year-old father from being by her side.

Mariani’s relief after the surgery was short-lived. His mother’s chest was opened again in April to fix the location of her pacemaker.

Back in the U.S., Mariani’s wife’s family battled against COVID-19. As she studied for her bar exam, the five-hour time difference made it impossible for them to talk as much as he wanted to.

While separated from his family around the world, Mariani was isolated in his downtown London apartment.

Public transportation grinded to a halt, shutting London down completely in March 2020.

Mariani took solace in his walks to Leathermarket Garden every Sunday, reading Sherlock Holmes surrounded by greenery, flowers and scampering dogs.

From March to August, he had no social interaction and was completely by himself.

“I couldn’t handle everything — being far away from my wife, being far away from my family in Brazil,” Mariani said.

He began counseling through the UF Counseling and Wellness Center May, he said.

“We have our pride and ego that we want to believe we’re very strong, but sometimes being vulnerable is extremely strong,” he said.

Whatever you need, be it coping with the loss of a loved one or dealing with a stressful job, the UF counseling center is fantastic, he said. The pandemic taught Mariani the importance of caring for his mental and physical health.

“I think people don’t realize that our lives are not the same, and they will never be the same,” he said.

Contact Alexandra Harris at aharris@alligator.org. Follow her on Twitter @harris_ alex_ m.

Brazil

Gabrielle Quadrado, (left) a 25-year-old climate science Ph.D. student, poses for a photo with her husband, Matheus Bose, (second from left), grandmother, Sonia Pereira, (third from left) and uncle, Leandro Pereira, (right). This was the last photograph Quadrado took with her uncle. (Photo courtesy to The Alligator)

With family and friends left behind in a country where smoldering unrest was fueled by the pandemic, tears flowed as guilt weighed down on UF student Juliana Rubinatto Serrano.

Brazil had the highest death toll in Latin America — reaching 513,000 deaths with 18.4 million cases since the pandemic began. Only about 12% of Brazil’s population have been fully vaccinated, according to Our World in Data.

President Jair Bolsonaro’s administration is under investigation for inefficiency and neglect in handling the pandemic.

“I remember when I was young — the talk about how Brazil was going to be the country for the future,” Serrano, a 23-year-old anthropology Ph.D. student, said.

She longs for accountability, impeachment and arrest of President Bolsonaro after he failed to secure vaccines in time, despite an offer from Pfizer.

She moved to Gainesville in August 2020 for her graduate program, worried returning home would financially burden her family during the pandemic.

Following a decade of economic deterioration, Brazil reached a record-breaking 14.7% unemployment rate. The cleaners, babysitters and other informal workers at the heart of Brazil’s economy lost their jobs in the pandemic, she said.

“Should I go back and try to help there? Or should I stay here and not cause any more problems with my family?” she asked.

The cost of goods has risen so much that many people can’t afford even the basics, where she has known of meat costing the same as gold.

Meanwhile, indigenous lands were destroyed and seized by illegal miners, loggers and ranchers, who profited under Bolsonaro’s lack of environmental laws, she said.

“Any time there is a health crisis, they’re the ones that suffer the most,” she said.

While guilt colored Serrano’s absence from Brazil, another UF international student moved back home to be with her family in São José dos Campos, Brazil, once the pandemic hit.

Camila Salviano, a 21-year-old business senior, moved to Gainesville in 2018 but returned home to her family in March 2020.

“In Brazil, the situation is like it was in March 2020,” Salviano said. “It’s still very bad.”

When her father got COVID-19, she said he was fortunate to recover at home and not in the hospitals, where she knew of many people dying from lack of equipment.

She hasn’t seen her family since moving back to Gainesville in January. On her final Christmas there, she noted her uncle, Stenio Cabianca, was having trouble speaking and eating.

Two years ago, he was diagnosed with amyotrophic lateral sclerosis. As she said her goodbyes, her heart felt heavy, wondering if she would ever see him again, she said.

She told him how much she loved him.

Cabianca was hospitalized one month ago. With patients sprawled across the hospital hallways, his organs failed after a three-week battle and he died at the age of 52 on June 9.

“The hardest part of all that was that I couldn’t be there,” she said. “All I wanted was to go back to Brazil and just be with my parents.”

Contact Alexandra Harris at aharris@alligator.org. Follow her on Twitter @harris_ alex_ m.

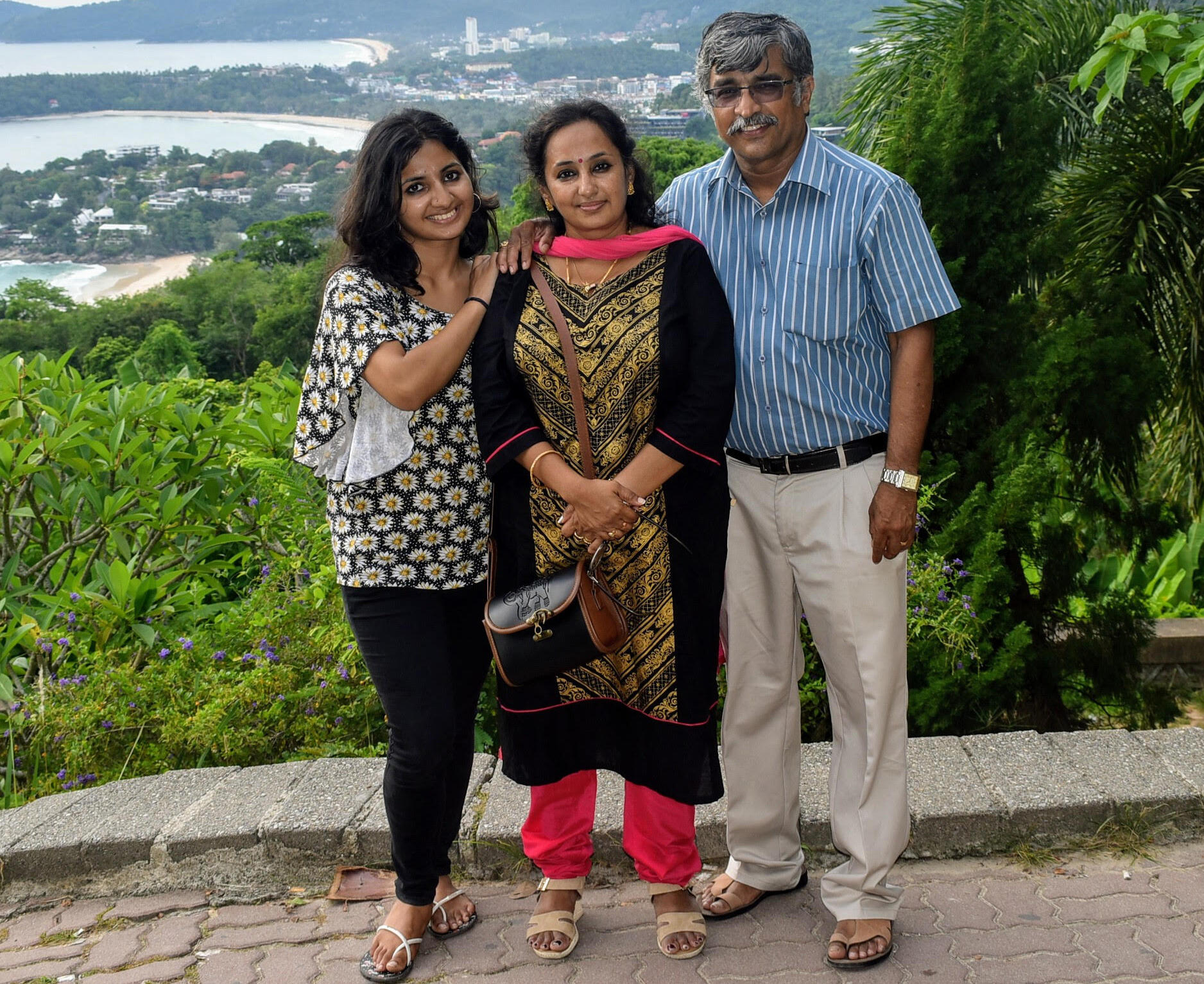

Camila Salviano, (right), a 21-year-old business senior celebrates her acceptance to UF with her mother, Glaucia Salviano, (left) and her father, Claudio Salviano, (middle). (Photo courtesy to The Alligator)

India

The hallowed Ganges River toted bloating corpses while pyre flames swallowed blackening bodies on each side of the road.

Even death did not bring a peaceful burial, UF student Ayswarya Nandanan said.

India had over 30.3 million COVID-19 cases with over 398,000 deaths. In May, India shattered the record for new infections at 400,000 a day, according to Our World in Data.

The official COVID-19 numbers are grossly undercounted from poor record-keeping and lack of widespread testing. The most likely estimate placed the true numbers at over 539 million infections and 1.6 million deaths, according to the New York Times.

Despite being one of the world’s leading vaccine manufacturers, only about 4.5% of the population is fully vaccinated. India has exported more doses than it has given to its own people.

The government filed an order for 11 million AstraZeneca doses and donated more than 60 million doses to more than 70 countries.

From Nandanan’s home in Kerala, India, the 24-year-old computer science master’s student completed her first semester at UF online.

“We were scared to even order newspapers,” she said. “To open the gate to my house, I wear a mask.”

Crematoriums were so packed that there was no space to bury the bodies, she said.

“I couldn’t take it,” she said. “Every morning waking up to see that this person died, that person died.”

The virus, with the prominent Delta variant indifferent to age, claimed the lives of her 88-year-old uncle and her 30-year-old coworker.

Nanandan received her first dose of AstraZeneca June 1 — one of three vaccines available, in addition to Covaxin and Sputnik V.

Once a shining beacon of economic growth in the world, India’s economy shrank by 7.5%, placing it among the worst-performing of major economies. Over 140 million people lost their jobs after the initial lockdown, with six million people still unemployed and small businesses crushed, according to the New York Times.

Economic despair left Nandanan’s local movie theater owner despondent. Under lockdown, ticket stubs went untorn and kernels unpopped, forcing him to close the business.

He committed suicide, unable to pay back his loan on the land, she said.

“This year has been so much more brutal,” Srijita Bhattacharjee, 25-year-old electrical and computer engineering Ph.D. student, said. “This time it has not spared any age.”

After arriving in Gainesville last August, Bhattacharjee wondered if all of her loved ones would be there when she returned home.

Her aunt recovered slowly from the virus at home, experiencing weakness for over a month. Government hospitals overflowed with patients, and many people were unable to afford private hospitals, she said. Many kept oxygen tanks at home.

People shared contacts for hospital beds and oxygen over social media. Strangers donated cooked meals and groceries to bedridden patients quarantined at home, she said.

“Everyone is so worried and sad,” Bhattacharjee said. “There’s not much space to be angry.”

Despite feeling isolated in Gainesville, she said international students are bonded by a shared understanding of how it feels to be constantly praying for the safety of their families back home.

“Don’t bottle up everything and think you’re the only person going through it,” she said.

Contact Alexandra Harris at aharris@alligator.org. Follow her on Twitter @harris_ alex_ m.

Ayswarya Nandanan, (left), a 24-year-old computer science master’s student poses for a photo with her family. (Photo courtesy to The Alligator)

2700 SW 13th St.

Gainesville, FL

32601

352-376-4482

editor@alligator.org